When it comes to New Year’s Resolutions, my lists tend to be way too long and complicated. Replace ginger snaps with green salads. Wear sunscreen even in the dead of winter. Walk more hills. Turn off the TV. Put the phone away. Brush the dog’s teeth every now and then. Don’t argue with strangers, or anyone else, on Facebook. Watch more sunrises and sunsets. Count blessings instead of troubles.

When it comes to New Year’s Resolutions, my lists tend to be way too long and complicated. Replace ginger snaps with green salads. Wear sunscreen even in the dead of winter. Walk more hills. Turn off the TV. Put the phone away. Brush the dog’s teeth every now and then. Don’t argue with strangers, or anyone else, on Facebook. Watch more sunrises and sunsets. Count blessings instead of troubles.

Worthy goals, all of them.

This year, though, I’ve decided to keep things simple by focusing on only one major goal. I want to read better so I can write better.

You can be a reader without being a writer, but you absolutely, positively cannot be a writer without being a reader. Writers read frequently—every spare minute, some days. Writers read widely, too, everything from the back of cereal boxes to the comic page in the newspaper to Tolstoy. And writers read deeply, the biggest challenge of all. They try to figure out how a particular author made a piece of writing work. Or failed to make it work. Because you can learn just as much from bad writing as you can from good.

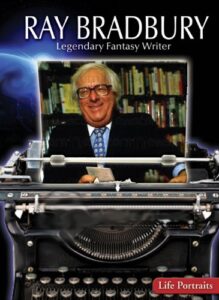

In 2024, I’m taking up a challenge issued by the late, great Ray Bradbury, who began his long and prolific writing career in the basement of a college library banging away on a typewriter he rented for ten cents per half-hour. To really understand how writing works and to inspire your own creativity, Bradbury said, you should—at the very least–read these three things every evening before bed: one poem, one essay and one short story.

Such an assignment need not be daunting. Sure, you can dive into “Beowulf” or “Paradise Lost” or “John Brown’s Body” if you want to study epic poetry. But you can also read Robert Frost or Shel Silverstein or Dr. Seuss. Limericks are poems. Nursery rhymes are poems. Songs are poems. You can check out poetry books from the library and find poems on the internet. So, yeah, reading poetry is a piece of cake.

The essay part of the assignment is also easy. Most any piece of relatively short, subjective, personal non-fiction—a reflection, a recollection, an observation–can be considered an essay. A newspaper column is an essay of sorts. So is a movie review or a political manifesto or a religious tract or the telling of a funny true story. I have lots of favorite essayists. Ann Patchett. David Sedaris. Rick Bragg. Abigail Thomas. My favorite essay collection? “One Long River of Song” by the late writer Brian Doyle. In second place is an amazing collection entitled “The Opposite of Loneliness” by Marina Keegan, who died in a car crash when she was only 22 years old. That book also includes nine of her short stories, all of which are wonderful.

Some readers love novels but resist short stories. I don’t know why. What’s not to like about finishing a complete piece of fiction in 20 or 30 minutes? I would point these resisters toward collections by some of the best-known “classic” writers of the twentieth century—Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, Sylvia Plath, Ernest Hemingway, and (yes!) Ray Bradbury himself, who wrote almost 600 short stories during his long lifetime, most of them on a typewriter he owned outright. But there are plenty of wonderful contemporary short story writers around, too. Ron Rash and Jill McCorkle are two of my favorites.

The best news of all is that if you’re searching for just one magnificent writer who has produced vast numbers of poems, essays, short stories AND novels, you need look no further than Port Royal, Kentucky, where 89- year-old Wendell Berry still lives and writes. I accept that no matter how long or how deeply I study him, his extraordinary talent is far beyond my feeble reach.

But it’s pure pleasure just to spend time with his words.

(January 6, 2024)