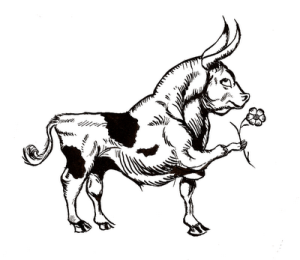

“Once upon a time in Spain there was a little bull and his name was Ferdinand. All the other little bulls he lived with would run and jump and butt their heads together, but not Ferdinand. He liked to sit just quietly and smell the flowers.”

“Once upon a time in Spain there was a little bull and his name was Ferdinand. All the other little bulls he lived with would run and jump and butt their heads together, but not Ferdinand. He liked to sit just quietly and smell the flowers.”

Thus begins “The Story of Ferdinand” by Munro Leaf. If you’ve ever had a kid or been a kid, you probably know it. Published in 1936, this children’s picture book was considered controversial by many adult readers who believed its messages of nonconformity and non-violence were “subversive pacifism.” I didn’t know that when my mother read it to me in the 1950s. It was the first bullfighting story I’d ever heard and I thought it was wonderful.

Here’s a summary. Grown-up Ferdinand accidently sits on a bee, which stings him and makes him puff and snort and paw the ground so crazily that he’s chosen to go to the bullfight in Madrid. The parade into the bull ring is led by banderilleros with sharp pins to stick in Ferdinand and make him mad. Next, astride skinny horses, come the picadors, carrying long spears to stick in Ferdinand and make him madder. Finally the matador, with his cape and sword, marches in. Ferdinand doesn’t give a care about any of them. He just plops down in the middle of the ring and sniffs the wonderful aroma of the flowers in the ladies’ hair and refuses to fight.

Unashamed, Ferdinand is sent home to live out his peaceful life in his quiet pasture.

It’s a sweet story, and I read it over and over when I was a child. I’ve read it many times to my own children and grandchildren, including the two in Denver who have their own copy of the book. I visited them at Christmas. I took with me “The Hemingway Stories,” a collection of the nineteen short stories featured in Ken Burns’s 2021 PBS documentary about Ernest Hemingway.

One of most unforgettable of those stories is “The Undefeated.” It’s also about bullfighting, though it’s nothing like Ferdinand’s tale. In it, an aging bullfighter returns to the ring after an injury, hoping to jump-start his flagging career. Readers can see and hear and feel and smell and almost taste the barbaric cruelty as the men mercilessly torture the bull and the crowd roars approval. Like many of Hemingway’s stories, this one is graphically violent and horribly depressing.

After I finished it, I found Josephine and Oliver’s copy of “Ferdinand” and read it to myself. Pondering the radical differences in the two stories, I set out for a solo walk around their neighborhood to clear my head. It had snowed a good bit and the street and sidewalks were icy. Mincing gingerly along so as not to fall and wondering all the while how I could have ever– even as a child–thought a story about the blood sport of bullfighting was cute and entertaining, I lost focus on where I was. All the houses on the cul-de-sac are of a similar contemporary Colorado style, with small front yards beside two-car garages. Most houses have a curved concrete sidewalk leading to the front stoop.

I made my way up one of those sidewalks, opened the door and stepped in. Three very large “doodle” dogs swarmed me, barking uproariously and wagging all over. Meg’s family doesn’t have three (or any) doodle dogs. The family sitting at the dining table stared at me speechlessly.

“I’m in the wrong house,” I stammered. “I’m so embarrassed. I’m Meg’s mother.”

“She lives next door,” one of the strangers said.

I didn’t tell them I made this mistake because I was thinking about bulls and banderilleros and picadors and matadors and children’s literature versus adult literature and not about which house I belonged in. I muttered “sorry” and stepped out onto the icy front stoop, determined to pay better attention the next time I took a walk.

(January 27, 2024)