Here we are, a month into baseball season, and I haven’t yet watched a single game on TV or in person. Not the Braves. Not UT or Tennessee Tech. Not Little League. I suspect I might be suffering March Madness sports overload.

Here we are, a month into baseball season, and I haven’t yet watched a single game on TV or in person. Not the Braves. Not UT or Tennessee Tech. Not Little League. I suspect I might be suffering March Madness sports overload.

I’d planned to celebrate Poetry Month, not baseball, in April by reading lots of poems and then writing about them. That didn’t happen. The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry, as the poet said. A snake in my house, the solar eclipse and Earth Day all got in the way. But on this fourth and final weekend of the month, the time seems right to write about one of my favorite poems.

And, no, it’s not “Ode to a Mouse,” penned by Scottish poet Robert Burns in 1785 after he accidentally turned up a mouse’s nest while plowing a field. That poem is written in archaic and complex language and is much too difficult for lazy me to wrestle with. I prefer the contemporary translation. Here’s the first line as Burns wrote it: “Wee, sleekit, cowran, tim’rous beastie.” See what I mean? Modern version: “Small, sleek, cowardly, nervous little beast.” But however you choose to read it, “Ode to a Mouse” is a lovely and compassionate poem, in which the poet apologizes profusely to the mouse for destroying her house.

In the next-to-last stanza is the aforementioned phrase: “The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men, Gang aft agley.” John Steinbeck liked the line so much he made part of it the title of one of the best little novels ever written.

But this column isn’t about Robert Burns or John Steinbeck (who wasn’t, as far as I know, a poet). It’s about Ernest Lawrence Thayer. A Harvard graduate with a degree in philosophy, Thayer moved to California in the 1880s to work as a humor columnist for his college buddy William Randolph Hearst at The San Francisco Examiner newspaper. Though Thayer considered journalism–not poetry–his forte, he occasionally wrote comic ballads for the paper. On June 3, 1883 his poem “Casey at the Bat” was published in The Examiner.

The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

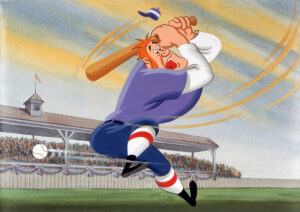

Second in popularity only to “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” Thayer’s salute to America’s pastime remains one of the most beloved poems of all times. It’s been recited for generations on stage and in elementary school classrooms and, in 1927, was the subject of a silent film starring Wallace Berry. It was made into a Walt Disney cartoon in 1946. And in 1998, “Casey at the Bat” was set to music and performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Yeah, but. Many critics of “real” poetry consider the work silly. Trivial. Lacking in artistry. Doggerel, in other words. Perhaps Ernest Thayer thought so, too. Though he lived until 1940, “Casey” was the last poem he ever wrote.

So why does it keep on keeping on? Perhaps because of its vigorous beat. Perhaps because it can be read quickly and easily understood. But I believe the main reason “Casey at the Bat” has had such amazing staying power is that its message still resonates. Casey thinks too much of himself. He’s arrogant. He’s pompous. He’s so cocky that he lets two perfectly good pitches go by without swinging. Casey’s hubris costs his team the ballgame and steals the joy from the town of Mudville. As another famous collection of poetry—the Old Testament book of Proverbs–put it long before there was such a thing as baseball: “Pride goeth before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall.”

All of which is to say it’s not too late to celebrate Poetry Month. Or baseball. Why not get your hands on a copy of “Casey at the Bat”? Or listen to James Earl Jones read it on YouTube. You might just discover it’s a pretty fine poem after all.

(April 27, 2024)