As Black History Month draws to a close, I confess with regret that I ran out of time to read and reflect upon “The 1619 Project” in this column, as I’d intended to do. The tempest over “Maus” and other Holocaust literature consumed most of my reading and writing hours and February slipped away.

As Black History Month draws to a close, I confess with regret that I ran out of time to read and reflect upon “The 1619 Project” in this column, as I’d intended to do. The tempest over “Maus” and other Holocaust literature consumed most of my reading and writing hours and February slipped away.

“The 1619 Project” was born in 2019 to mark the 400th Anniversary of the arrival of the sailing ship “White Lion” on the shores of the Virginia colony. That ship held about two dozen enslaved persons, kidnapped in West Africa and brought across the ocean in chains to be sold to the American colonists. An undocumented number of Africans died on that voyage, some from starvation, others from illness and still others by willfully throwing themselves into the churning waters to drown.

The New York Times, committed to the idea that this momentous anniversary is a vital and inextricable part of American History, published more than 100 pages of essays, short fiction and poetry related to the birth of slavery in this country. The project was later expanded to a 500-page book that has, since its publication, been enthusiastically received and also highly controversial.

With outcries against “Critical Race Theory”– a complicated academic/legal term that many of its fiercest opponents fail to understand–state legislatures, local school boards and worried parents continue to propose laws and policies designed to keep students from kindergarten through college (yes, college!!!) from learning how minorities in this country have been treated for centuries. Why? They worry that learning these truths might make white students feel uncomfortable about what their ancestors did.

Opponents of CRT have banned or attempted to ban countless works of fiction and nonfiction that lay bare the truth, wrongly believing that by sweeping it under the rug, we can pretend the ugliness never happened.

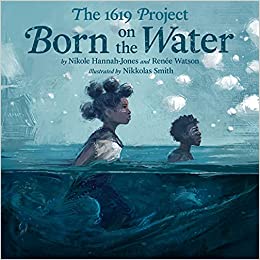

Perhaps, thought NYT journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, the leading force behind “The 1619 Project,” a children’s book might make the story of slavery in America easier to talk about. So she joined forces with fellow writer Renee Watson and illustrator Nikkolas Smith to create “Born on the Water,” a picture book in verse aimed at elementary school-aged children.

The story begins when a young Black girl is given a school genealogy assignment: Where did her people come from? Her grandmother gathers the family around and tells of how, centuries ago, their people lived in the kingdom of Ndongo in West Central Africa. “Their story does not begin with whips and chains,” the grandmother says. “Before they were enslaved, they were free.” The people lived happily and productively, making tools and farming and cooking and dancing and singing and playing musical instruments. They held their families and their fellow villagers close. “And the white people took them anyway,” Grandma says. “Kidnapped them. Baptized them in the name of their god. Stamped them with new names.” And then she sums it up: “Ours is no immigration story.”

Though I’ve read and watched countless slavery stories much rougher than this one, “Born on the Water” made me uncomfortable. That’s why it’s so vitally important. How can we do better without acknowledging the sins of the past? This book and others like it are not intended to be guilt trips but cautionary tales. We must all—and when I say all, I include children—understand that there was a time in America when some people, even people who wrote such lofty phrases as “All men are created equal,” thought it acceptable for human beings to own other human beings.

“Born on the Water” is, ultimately, not a sad story. It’s a story of resilience, resistance, legacy and pride. It deserves a place of honor in classrooms and libraries and in the homes of anyone committed to working to overcome the devastating mistakes of our past.

(February 26, 2022)