When Darnell Arnoult asked me to write a review of “Galaxie Wagon,” her newest collection of poems published in February by LSU Press, I was hesitant at first. Not that I doubted the poems would be fabulous. I’ve known Darnell for many years as a teacher, mentor and dear friend. She’s the Writer-in-Residence at Lincoln Memorial University whose myriad publication credits include one other poetry collection, “What Travels with Us” (LSU Press, 2005) and the novel “Sufficient Grace” (Atria Books, 2007). She’s one of the most gifted writers I know.

When Darnell Arnoult asked me to write a review of “Galaxie Wagon,” her newest collection of poems published in February by LSU Press, I was hesitant at first. Not that I doubted the poems would be fabulous. I’ve known Darnell for many years as a teacher, mentor and dear friend. She’s the Writer-in-Residence at Lincoln Memorial University whose myriad publication credits include one other poetry collection, “What Travels with Us” (LSU Press, 2005) and the novel “Sufficient Grace” (Atria Books, 2007). She’s one of the most gifted writers I know.

But I’m no poet. Nor am I a student of poetry. What business did I have reviewing her book?

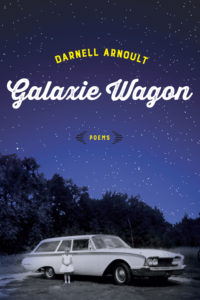

Sinking into a rocking chair last weekend, the slim volume with the fabulous cover in hand, I quickly discovered you don’t need to know a thing about poetry to fall in love with “Galaxie Wagon.” It’s an impossible-to-put-down autobiography in verse.

Take “The Gorilla Story,” for instance, which tells about a night in 1957 when Darnell’s daddy wrestled a gorilla—and won!—but didn’t collect the $100 he was promised because the carney in charge of the show claimed he’d had an illegal hold on the ape. Or “How I Would Sculpt Beauty,” in which she describes her mother: A figure of a woman at a small sink in the only bathroom of a small house on Chestnut Street. She would stare, open-mouthed, into the medicine chest mirror, rubbing her spit with the small black brush into the tar of Mabelline mascara.

In “MG,” Darnell recounts how her brother taught her to drive an old Ford Falcon, a car so beige it might as well be invisible. Find the sweet spot, he tells her, where the clutch catches. Then he warns her to worry about where you’re going, not where you are. You go where you look.

I might not know much about poetry, but I know good stuff when I read it.

My favorite poems in the collection are about romance and horses. I knew that Darnell met her husband, “Cowboy,” on the internet and that love blossomed quickly. I also knew he was an experienced equestrian. But now that I’ve read “Galaxie Wagon,” I know the rest of the story.

“Episodes” tells of how Darnell grew up loving TV westerns. I longed for a cattle drive, a wagon train, a galloping palomino with a flowing mane, she writes. In “Call and Response,” she answers Cowboy’s questions in an online conversation. Do you like horses, fishing, sitting on the porch watching it rain? he writes. She replies Once upon a time I had a palomino Shetland pony named Buck Shot [who] threw the neighborhood kids as often as we climbed into the saddle…I have loved cowboys all my life. “Terrain” describes her terror while riding a horse on a steep downhill in the mud. You can’t just go on flats and ups, Cowboy tells her. You can’t think about what might happen till it does… Worry’s what kills.

My best of the best award goes to “How I Came to Saddle a Horse at the Bar J.” It just might be my favorite poem ever, by anyone. The narrator has hired a man to give her horseback lessons. He’s figured out she knows little about horses and that she’s agreed to take a week-long ride into the wilderness with a man she barely knows. How do you know he ain’t some axe murderer?” her teacher asks while showing her how to groom and tack and sit a horse. The poem concludes like this: Three months go by. Before we leave, he tells the man who’s asked me to ride in the wilderness, I don’t think she’ll embarrass me, but if you forget the sandwiches, God’s sakes, don’t send her back alone to get nothing.

See what I mean? It’s really not all that hard to understand poetry. Or to love it.

(April 10, 2016)