Will the recent uproar over Governor Bill Lee proclaiming July 13 “Nathan Bedford Forrest Day” in Tennessee die down, or is it likely to remain a hot-button issue into 2020? Under pressure from those who consider Forrest more villain than hero, Lee has said he’ll work with legislators to change a 1931 statute requiring the governor to sign proclamations for six days of “special observance.”

Will the recent uproar over Governor Bill Lee proclaiming July 13 “Nathan Bedford Forrest Day” in Tennessee die down, or is it likely to remain a hot-button issue into 2020? Under pressure from those who consider Forrest more villain than hero, Lee has said he’ll work with legislators to change a 1931 statute requiring the governor to sign proclamations for six days of “special observance.”

In addition to Forrest Day, the others are: Robert E. Lee Day (January 19), Abraham Lincoln Day (February 12), Andrew Jackson Day (March 15), Confederate Decoration Day (June 3) and Veterans Day (November 11). Length limitations for this column won’t allow me to comment upon these other days of observance, except to say I think there could have been–in at least a couple of cases–better choices.

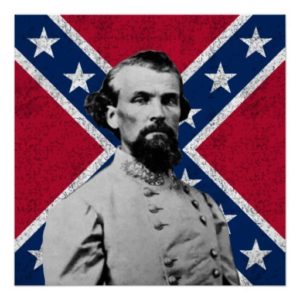

Here’s what we know about Nathan Bedford Forrest. Born in middle Tennessee in 1821, Forrest honed his slave trading skills in Mississippi. He moved to Memphis in 1852 and amassed a fortune operating a slave market there. Estimates are that he bought and sold 7,500 “negroes” during the years his market was in business. By 1860, Forrest owned two plantations and was one of the wealthiest men in Tennessee. He was euphemistically known as a “stern disciplinarian” in regard to the slaves he owned and traded. By all accounts, he was enthusiastic about the whipping post and had no reservations about splitting families apart.

Though Forrest had no formal military training, he enlisted in the Confederate Army soon after the Civil War began. His equestrian talents (he was known as the “Wizard of the Saddle”) and daring battle tactics quickly propelled him from the rank of private to that of lieutenant general. Military historians consider Forrest one of the greatest cavalry generals of the war. He led troops at the battles of Shiloh, Chickamauga, Second Franklin, Vicksburg and others.

But what happened at the Battle of Fort Pillow on April 12, 1864 plagued Forrest for the rest of his life. In what has been called “one of the bleakest, saddest events in American military history,” Forrest’s men overran the Union garrison near Henning, Tennessee and demanded unconditional surrender. When the soldiers in blue—the majority of whom were members of the United States Colored Troops—threw down their arms, they were shot or bayoneted by Confederate soldiers. Almost three hundred men were massacred in cold blood.

After the war, Forrest worked as a lumber merchant and served as president of a railroad in Memphis. When the Ku Klux Klan was formed in 1866 to terrorize blacks and oppose Reconstruction efforts, Forrest became its leader. The Wizard of the Saddle was now the Grand Wizard of the KKK.

Forrest’s businesses eventually failed and he took a job as overseer at a prison labor camp. He died in 1877 at the age of 56.

There are those who contend that doing away with Nathan Bedford Forrest Day whitewashes history. They are likely some of the same folks who’ve fought the removal of the bust of Forrest from the rotunda of the state capitol since it was placed there in 1978. The plaque beneath the bust simply reads:

LIEUTENANT GENERAL NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST

1821-1877

CONFEDERATE STATES GENERAL

No mention of slaves. No mention that the army he helped lead was in rebellion against the United States of America. No mention of the KKK. What Forrest did needs to be remembered, but it does not need to be glorified. The best place to learn the truth about him would be an exhibit at the Tennessee State Museum.

When the General Assembly reconvenes in January, Bill Lee has a chance show courage that’s been lacking in our governors for almost 90 years. He should take Nathan Bedford Forrest’s day away from him. And give it to someone who deserves it.

(July 28, 2019)