Challenge: What can I write about the recent firestorm over “Maus” that hasn’t already been said?

Challenge: What can I write about the recent firestorm over “Maus” that hasn’t already been said?

Perhaps I should hearken back to when daughter Meg, now closing in on her 38th birthday, was in sixth grade at Capshaw School. Her class read “Number the Stars” by Lois Lowry. It piqued her interest in Nazi Germany, so she went on to read “The Diary of Anne Frank” and “The Hiding Place” and several other such books. Those books upset her so much that I suggested she might want to take a break from Holocaust literature.

But never once did I suggest–or think—that she ought not read those books. “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” and “The Book Thief” and “Night” were added to her list later. And you know what? Meg has never once spoken the words “Heil Hitler!” or waved a Nazi flag or spray-painted a swastika on a synagogue.

Maybe the fact that she doesn’t do those things is unrelated to her learning the truth about Adolph Hitler’s calculated extermination of more than six million Jews, but I don’t think so. That’s why I can’t imagine why anyone, especially a Board of Education in the United States of America, would think it appropriate to remove “Maus” or books like it from the curriculum. When I learned that the School Board in McMinn County had done just that, I began scrambling to get my hands on a copy. It wasn’t easy. Bookstores were sold out. The waiting list at the library was long.

When a friend who teaches at Cookeville High School learned that I was searching for a copy of “Maus” so I could write this column, she drove to my house in the snow to lend me hers.

I was in error last week when I referred to it as a graphic novel, though I’m not the only one who’s called it that. Originally published in 1980 in serial form and then in 1996 as a two-volume book, Art Spiegelman’s story is part biography, part history, and part memoir. It’s not fiction. Spiegelman’s parents were Polish Jews who spent most of World War II hiding in the ghettos. In 1945, they were captured and sent to Auschwitz. Both survived, but their five-year-old son Richieu was intentionally poisoned by his aunt while under her care so he wouldn’t be sent to the death camp.

Art Spiegelman was born in Sweden in 1948 and immigrated to the United States with his parents not long afterwards. He became proficient at drawing underground comics at an early age. “Maus” won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992 in the “unclassified” category. It was the first and only (so far) graphic work to be awarded the Pulitzer.

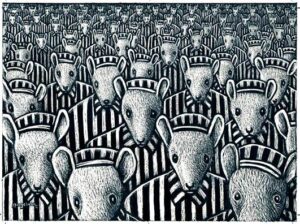

Does the fact that this Holocaust story is told in pen-and-ink drawings, with Jews portrayed as mice and Nazis as cats, make it more likely to attract and hold the interest of middle school and high school students? Perhaps. But the comic book format doesn’t make the story any less horrifying. And that’s the point. No one should finish school without learning about the atrocities Hitler and his henchmen orchestrated. Any school board or administrator that believes otherwise is not protecting students, but doing them an immense disservice.

The push-back over the book banning in McMinn County has been enormous and gratifying. Free copies of “Maus” have been offered to all students there who want them. The author has spoken via the internet to countless interested listeners.

But in other news, controversial books continue to be removed with reckless abandon from classrooms and school libraries around the country. If you think it can’t happen where you live, you’re wrong. We must allow the truth be written and read, no matter how unpleasant that truth might be. We must stand fast against book banning. Before it’s too late.

(February 12. 2022)