One of my duties with the Putnam County Election Commission during early voting is traveling with co-workers to nursing homes and assisted living facilities to help residents cast their ballots on-site.

One of my duties with the Putnam County Election Commission during early voting is traveling with co-workers to nursing homes and assisted living facilities to help residents cast their ballots on-site.

Though most voters come to the commons area where we’re set up, we’re happy to visit the rooms of those who are bedridden. The rooms are almost always personalized in interesting ways. Greeting cards and photos hang from the walls. Colorful blankets and pillowcases brighten the beds. Many residents display interesting collections. We recently visited a room where the voter had draped dozens of beautiful necklaces over various pieces of furniture. Another had a collection of frogs. (Not real frogs.) Yet another had bunnies all over the room. (Not real bunnies.)

But no matter how individualized, all the rooms have one thing in common. A television, which is often blaring at full volume. The show that’s on more than any other? It’s one that grabs hold of me the minute I walk through the door and makes me want to hang around even after the voting is done and we’ve packed up all our stuff to leave.

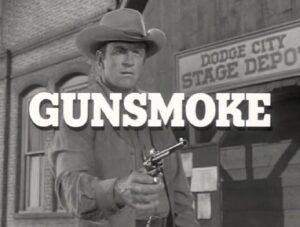

Gunsmoke.

No surprise, right? Because millions folks of a certain age—my age included—adore that show. Many fans have, no doubt, seen all 635 episodes. Perhaps all 635 episodes over and over again. CBS began broadcasting half-hour episodes of Gunsmoke in 1955. In 1961, the show expanded to one hour. In 1966, it went from black-and-white to color. Gunsmoke ended production in 1975, making it the longest-running western in television history.

During those twenty years, James Arness never missed a single episode. Not one. As sure as the sun comes up in the morning, Marshal Matt Dillon bravely and faithfully maintained law and order in Dodge City.

In the early 1960s, my great-grandparents often came to visit. Because travel was hard for them, they usually stayed with us for several weeks at a time. Our little house was crowded but fun when they were there. “Big Dad” was deaf. Not just hard of hearing, but completely and irrevocably deaf. He loved Gunsmoke. He’d move a dining chair from the kitchen and position it as close to the TV as possible so he could read the actor’s lips. He followed the stories amazingly well, but if and when he got confused, he asked whoever was in the room with him—usually my brother Rusty and me—what had happened.

The answer needed to be written down quickly so he could read it and continue following the plot. Since Rusty was only four and couldn’t write, the job fell to seven-year-old me. I relished it. I kept a lined notepad and sharpened pencil at the ready and as soon as Big Dad said he needed me, I wrote down what had just happened and showed it to him. Things like DOC’S BEEN SICK or THEY DON’T KNOW WHERE CHESTER IS or THE WELL’S GONE DRY.

This meant I had to pay attention to plot and dialog and even the dramatic music that accompanied dramatic scenes and report what I’d heard, accurate and fast. Sometimes I wonder if Gunsmoke might have jump-started my writing career.

I do know that, like most every other female in America from age seven to 107, I had a huge crush on Matt Dillon. He was tall and strong and smart and handsome, but not in a pretty-boy way, and—most importantly–unafraid of any bad guy who crossed his path. Residents of Dodge City could sleep easy with Marshal Dillon in charge.

Gunsmoke memories come flooding back whenever I visit a nursing home. These days, closed captioning allows viewers who can’t hear to follow the story without the help of a child reporter with a notepad. That would have come in handy for Big Dad.

But I like to believe he enjoyed our way of doing things even better.

(July 20, 2024)