It’s been almost fifty years since I started seventh grade. That realization is shocking in and of itself, but even more shocking is that I still remember a lot of stuff I learned back in 1966 at Forest Hills Elementary School in Augusta, Georgia.

It’s been almost fifty years since I started seventh grade. That realization is shocking in and of itself, but even more shocking is that I still remember a lot of stuff I learned back in 1966 at Forest Hills Elementary School in Augusta, Georgia.

It was the first time my peers and I got to change classes. Miss Smith, a middle-aged spinster who smelled like Ivory soap and whose jet black eyebrows were drawn on with a heavy hand, taught math and English. Thanks to her, I mastered long division and solving for the “x” in simple equations. And I learned how to write an essay and diagram a complex sentence.

Miss Smith was also my homeroom teacher, so it was she who took attendance, collected lunch money, led us in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance and—here’s the biggie—read a couple of Bible verses and said a short prayer every morning. That the U.S. Supreme Court had recently ruled such actions in violation of the Constitutional principle of separation of church and state wasn’t even on our radar.

Several of my classmates were Jewish. I know this because seventh grade was the year for bar mitzvahs and bas mitzvahs and the requisite post-ceremony parties, to which the whole class was always invited. I can’t remember if, out of respect for those students’ faith, Miss Smith read aloud only from the Old Testament or whether she left Jesus out of her prayers. Somehow I doubt it but, to my knowledge, no one ever complained.

The name of the teacher who taught social studies and science is lost to me, so I’ll call her Miss Jones. She was young and pretty and wrote so beautifully on the blackboard that her lecture notes were almost a work of art. I don’t remember much about Miss Jones’s science lessons other than that we learned to name the planets (including Pluto) by memorizing the sentence “My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nine Pickles.”

But I do remember social studies.

We studied World Geography that year, which involved not only learning where continents and countries and oceans were on the map, but also about the culture and religion of people who lived in faraway lands. I don’t recall much of what was said about Hinduism or Buddhism or Taoism. And though I’m certain we discussed Judaism and Christianity, those lessons had little impact on me, perhaps because—as a child who’d gone to Sunday School and church all my life— it was too familiar to be interesting.

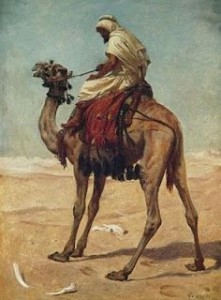

Not so for our study of “Moslems,” exotic, swarthy-skinned people who lived in desert lands like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iran and Iraq (which we pronounced EYE-ran and EYE-rack and which were largely indistinguishable in our minds). Moslems rode camels, wore long flowing robes, prayed in mosques topped by minarets and worshipped one god, whom they called “Allah.” They had a prophet named Mohammad and a holy book called the Koran.

We learned about world religions in a very matter-of-fact way, with no judgment as to whether the faiths of foreign people were right or wrong, good or evil. And no mention—none that I can recall, anyway—was ever made that some of those “foreign” faiths were represented right here in the good ole USA. Even in the 1960s.

I have no idea how the social studies textbook I studied in seventh grade might compare with “My World History and Geography: The Middle Ages to the Exploration of America,” which has recently stirred up a hornet’s nest in White County.

But it sure seems like a good topic for a future column.

(November 1, 2015)