When it comes to things that might fall out of the sky and hit a person on the head, the list is long. Precipitation. Tree branches. Nuts. Pine cones. Bird poop. Rocks, if you’re hiking in the mountains.

When it comes to things that might fall out of the sky and hit a person on the head, the list is long. Precipitation. Tree branches. Nuts. Pine cones. Bird poop. Rocks, if you’re hiking in the mountains.

But never had it occurred to me that an iguana might come crashing down on my noggin.

That was the warning from the Sunshine State last week, only a few days after I’d returned from a visit. My friends and I spent a couple of hours at Everglades Wonder Gardens in Bonita Springs. Opened in 1936, it’s one of the oldest roadside attractions remaining in Florida and features a lovely botanical jungle that lets visitors get up close and personal with a variety of animals. There are birds galore, including ducks, ibis, strutting peafowl and fabulous flamingos that eat right out of your hand. Even more interesting are the reptiles. Tortoises. Snakes. Alligators, of course. And a teenaged iguana named Buddha, who’s been at the Wonder Gardens for several years.

As Buddha stared at me from his fenced enclosure, my mind raced back to iguana stories from my past. Many years ago, these same friends and I were strolling the Gatlinburg Trail one sunny afternoon when we came face to face with a middle-aged woman cradling something wrapped in a baby blanket. It clearly wasn’t a baby. At first, we thought it might be a dog. But when I asked what she was carrying, the woman folded the blanket back to reveal the scaly green face of a very large lizard.

I took a quick step backwards. “Ummm…what is that?” I asked.

“An iguana,” she answered matter-of-factly, as though it was perfectly normal to be ambling through the Great Smoky Mountains with a huge tropical lizard in your arms. Then she walked on.

Even more memorable is the story of Louise, an iguana that belonged to a young man named Jason who lived in a little cabin that hung off the side of a mountain in West Virginia. Jason had kept Louise as a pet for several years, which is no easy task. Iguanas have strict environmental and dietary requirements. Because they can grow up to seven feet long, iguanas need a big cage with heat lamps, water misters, a bucket to use as a toilet and fresh salads served at the same time every day. Jason did his best to care for Louise, but he worked long hours away from home and perhaps didn’t give her all the time and attention she craved. Louise grew mean. She took to whipping her strong tail or scratching Jason whenever he took her out of her cage. She bit him almost every day, sometimes so aggressively that his wounds required stitches.

After a while, Jason decided he’d had enough. Iguanas can live up to age 20. Jason couldn’t see himself spending the next several years being attacked by a hostile reptile. So he did the only thing he could think of. West Virginians take pride in feasting on squirrel, groundhog, possum and other unusual fare. “I had Louise for supper one night,” Jason told me. “And not as a guest.”

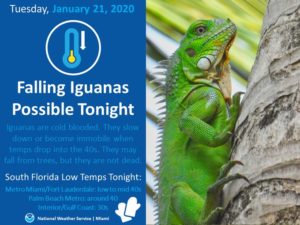

That disturbing memory washed over me when I heard on the news that comatose iguanas were tumbling out of trees when temperatures in south Florida reached the low 40s. Because they’re cold-blooded, iguanas go into a state of brumation (semi-hibernation) when the weather’s cold. They’re unable to grasp onto the tree branches where they roost, so they fall and lie stiff and unmoving on the ground until temperatures rise.

“Whatever you do, don’t pick them up!” wildlife officials warned residents and tourists. “Once they thaw out, iguanas are likely to bite.” A warning Jason was, no doubt, affirming all the way from wild and wonderful West Virginia.

(February 2, 2020)